|

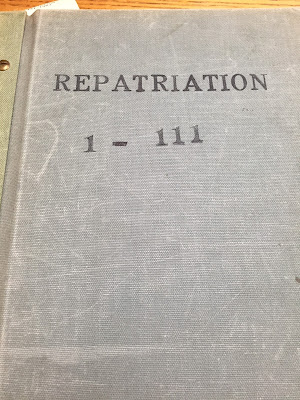

| Repatriations from San Bernardino, California. (c) Gena Philibert-Ortega. |

American women's repatriations is a research topic that I am passionate about. It's one that has led me to NARA regional offices, county archives, and other repositories. It's the topic that I research, read about, and question the most. There was a time where American women were stripped of what little citizenship rights they had, simply because of who they chose to marry. Their stories are the ones I want to uncover.

First, let's address the subject of women's citizenship.

Prior to 1922, you are less likely to find naturalization papers for a female ancestor because of derivative citizenship. The idea was that a non-citizen woman who married a US citizen, received citizenship as a result of that marriage. If her husband was not a citizen but naturalized during their marriage, she was included in that naturalization. From 1855 to 1922 immigrant women who married American citizens became American citizens. But in 1907, The Expatriation Act stated that derivative citizenship would not only affect the immigrant woman but also the woman who was an American citizen by birth. This meant that American women who married a non-US citizen lost her US citizenship.

Where did this come from? Well, in 1915 the Supreme Court ruled that "marriage of an American woman with a foreigner is tantamount to voluntary expatriatism." American women who would marry foreign men and retain their citizenship "would allow them to aid or protect German spies." *

How many women did this law affect? A precise number is not known but according to Ann Marie Nicolosi’s article, We Do Not Want Our Girls to Marry Foreigners: Gender, Race, and American Citizenship, a look at the 1920 U.S. Census suggests that around eighty-nine out of a thousand children were born to American mothers and foreign born men. In the 1910 census, nearly six million children had one native born parent and one foreign born parent.

Some of this changes with the passage of the Cable Act in 1922. The Cable Act signaled the end of women’s derivative citizenship and gave women the right to apply for their own naturalization. The Cable Act, also known as the Married Women’s Independent Nationality Act was a start but it would still take additional legislation before all women who had lost their citizenship could be repatriated.

Initially, the Cable Act allowed women who lost their citizenship to go through the naturalization process just as if they were never US citizens. However, this did not include all women. Women who had married men ineligible for citizenship, were still not allowed to apply for citizenship. It would not be until

1936 that women were finally allowed to forgo the lengthy naturalization process and repatriate by taking an oath of allegiance if and only if their husbands were dead or they had divorced. Four years later, in 1940, women could repatriate no matter what their current marital status. I can tell you from my own research that women were still repatriating well into the 1970s.

|

| A 1939 repatriation from San Bernardino, California. (c) Gena Philibert-Ortega. |

So what records did this leave behind? Your affected female ancestor may have left behind a naturalization record or an allegiance form (complete with a form that lists birth place and date, her marriage date and spouse's name).

Did all of the women take steps to regain their citizenship? I now at least in the case of one woman I know about, she never did. Possibly she didn't know she lost her citizenship or maybe she didn't care to go through the process.

Once again, knowing about the history of the time makes a difference when we research women's lives.

References

Christina K. Schaefer, The Hidden Half of the Family: A Sourcebook for Women’s Genealogy.

When Saying I Do Meant Giving Up Your US Citizenship by Meg Hacker. Prologue Magazine. (PDF)

* “9 Facts about Jeanette Rankin, the First Woman elected to Congress,” Mental Floss

No comments:

Post a Comment