|

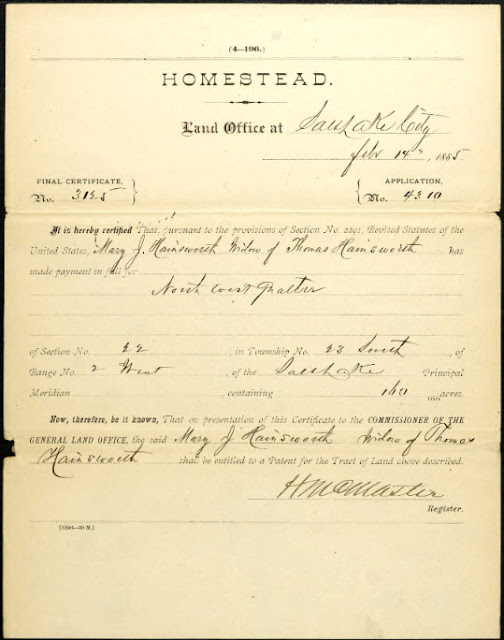

| From the collection of Gena Philibert-Ortega |

There are different types of cemeteries. It's important to know the types because that can be a clue to what records could exist. They include:

- Church Cemetery

- Public Cemetery

- Customary Cemetery

- Private Cemetery

- Lodge Cemetery

- Ethnic Cemetery

- Family Cemetery

- Veterans Cemetery

- Mass Grave

In some cases a cemetery may have sextant records which could range from an index entry, an index card with burial information, or a record with data gleaned from family, the funeral home, or the death certificate.

Having written a book about cemeteries, I'm always amazed when we can find the grave marker for an ancestor. Not all markers stand the test of time. Some graves never get marked, which happens if there is no money for a stone or if someone has outlived other close family members. If the grave was marked with a wood marker, that marker would have deteriorated over time. If there was any metal in the marker, there's a chance that it was stolen by those looking to make some money from the metal inserts. Sometimes markers are stolen by people for whatever reason. In the case of a female ancestor in my family, her marker simply is gone. When asked about its location at the cemetery office, I was told that "those people died a long time ago and no one paid to have their graves kept up" (endowment care). That was for someone who died in the early 20th century.

My ancestor's final resting place includes burials that are now under a golf course and my favorite, under a rising river. So it's not surprising when we can't find burials.

|

| A cemetery record. From the collection of Gena Philibert-Ortega |

So here are my recommendations:

- It's fine to start with websites for possible photos of a marker but don't stop there. Websites to check include: FindAGrave, Billion Graves, Interment.net, and the US GenWeb Cemetery Transcription Project.

- Search the FamilySearch Catalog for the city your ancestor lived and then click on the subject Cemeteries to find transcriptions of cemeteries.

- Search PERSI for cemetery transcriptions. PERSI is found on Findmypast.

- Check old Plat maps. They show cemeteries.

- Ask locals. They may know of a cemetery on a person's land that might not be obvious from cemetery listings.

- Know the history. For example, San Francisco has only a few cemeteries because the burials were moved to Colma in the early 20th century so that the dead didn't take up valuable real estate. Knowing the history of a place can prevent frustration over not finding what you think should be there.

If the area's death certificates are online via FamilySearch or other websites, look through those around the time of your ancestor's death. Notice the burial information. That might help to understand where people were buried during that time.

Lastly, don't forget the newspaper. Remember that it's more than an obituary search, especially if she lived in a small town. Researching a death means searching for the obituary but look in the days prior to that for mentions of an illness, accident, or crime that resulted in the death. After the obituary you might find a legal notice for a probate action.

Resources

The Ancestor Hunt

MySendOff - The 15 Types of Cemeteries